[ YOU ARE HERE: Houghton Heritage > Articles > Bernard Gilpin > The Gilpin Crest ]

![]()

[ YOU ARE HERE: Houghton Heritage > Articles > Bernard Gilpin > The Gilpin Crest ]

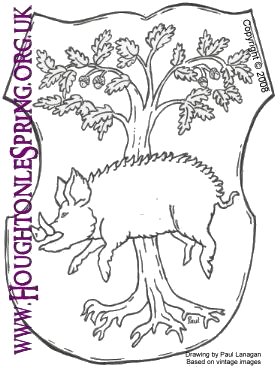

Drivers passing through Houghton can’t help but have noticed the newly erected signs on the A690, welcoming visitors to the “ancient town of Houghton-le-Spring”. The sign at Houghton Cut replaced an old one which snapped in half in 2008 (for a while only ‘HOUGH’ was visible). Another has been placed near to Rainton Bridge. Both of the new signs feature the boar and oak tree from the family crest of Bernard Gilpin. Reverend Bernard Gilpin, the Apostle of the North and Father of the Poor, is Houghton’s most well-known Rector. Copyright © Books of the North 2009-2010

|

At around the time of the signing of the Magna Carter (1215 AD), Bernard Gilpin’s ancestors resided in Kentmere Hall, Westmorland (Cumbria), a long way away from Bernard’s arrival in Houghton in 1558. Copyright © Books of the North 2009-2010 Richard De Gilpin, who was also known as Richard the Rider, achieved prominence for slaying the 'Wild Boar of Westmoreland' a ferocious porcine which was terrorising local villages and ravaging the land with its tusks. The Baron of Kendal rewarded Gilpin’s bravery and gave him land in and around Kentmere. King John granted Gilpin a coat of arms, which featured the sable (black furred) boar and a crescent moon, on a gold background. Research suggests that the oak tree, which pierces the boar on modern crests, was not part of the original Coat of Arms. Copyright © Books of the North 2009-2010 |

The Wild Boar Hotel near Windermere is thought to have been built on the site where the beast was killed.

![]() ........

........ ![]()

![]() ........

........ ![]()

The Gilpin crest has now been adopted by Houghton and can be found in a variety of places including: Copyright © Books of the North 2009-2010

|

This article has moved to a new location. Visit it by clicking HERE.

|

Parts of the Gilpin crest were even incorporated into the civic arms for Sunderland Metropolitan Council, when Houghton became a part of Sunderland upon the reformation of local government in 1974 (the design was subsequently changed in 1992 when Sunderland became a City). Copyright © Books of the North 2008.

|

Houghtonian, Joan Lambton, is the proud owner of a hand-made fired clay version of the Gilpin crest, but has recently discovered that her crest is not as unique as expected, even though her own mother had made it! While in the Gilpin Press printers, she noticed a similar crest mounted on the wall. |

Joan has since discovered that three versions of the crest were fired – her own, the one in Gilpin Press, and a third which her mother used to possess but is now missing.Copyright © Books of the North 2008.

.....

.....

A fine example of the crest can be found engraved upon the west side of Bernard Gilpin’s tomb, located in the south transept of St Michael’s Church. The version on the tomb, which could date from Gilpin’s death in 1583, features a slightly portly boar upon an ornate shield. This crest was sketched in detail by the famed artist Samuel Grim in around 1780, and luckily so, as the engraving is now in a damaged condition.

If you have enjoyed this article and would like to make a donation to Houghton-le-Spring Heritage Society, please click DONATE for PayPal or to have your name recorded in the Book of Benefactors & Supporters click BOOK:

With thanks to Dianne Sutherland and Joan Lambton for information.

[ YOU ARE HERE: Houghton Heritage > Articles > Bernard Gilpin > The Gilpin Crest ]

PAGE UPDATED: 29/10/2012

Richard de Gylpyn (the name already undergoing slight change), called "Richard the Rider," performed a signal act of bravery in the time of King John, killing the last wild boar of Westmoreland, which had devastated the land and terrified the people.

The Wild Boar of Westmorland is a legend concerning Richard de Gilpin and the villagers and pilgrims visiting the ruins of the Holy Cross at Plumgarths, and the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin on St. Mary's Isle on Windermere.

The story goes that in the reign of King John (1199-1216) a ferocious wild boar infested the forest between Kendal and Windermere, it had its den in the neighbourhood of the well known as Scout Scar. Tales of the monster’s malignant and unwonted ferocity were circulated far and wide, pilgrims paid their devotions at the Holy Cross before embarking upon the perilous journey through Crook and over Cleabarrow; the creature's main haunt. It is said that "inhabitants (of the local villages) were never safe from its attacks, and that pilgrims... shuddered with fear"

De Gylpin determined to free them from these attacks, and tracked the monster through the forest. After a dramatic fight he slew the animal on the spot of the Wild Boar Inn, on the banks of the little stream, ever since known as the Gilpin. After these brave exploits Richard de Gilpin changed his family crest to include a black boar on a gold background. He was rewarded the lordship of the manor of Kentmere by the Baron of Kendal for his exploits. The event was immortalised in a song known as the "Minstrels of Winandermere"

George Carlton, Bishop of Chichester (1619–1628), wrote a life of Richard's descendant the famous Bernard Gilpin, in it he said that Richard "“slew a wild boar raging in the neighbouring mountains like the boar of Erymanthus, brought great damage upon the country people, and was as a reward for his services given the manor of Kentmere by the then Baron of Kendal.”"

The Gilpin Family

The valley is famous for the Gilpin family who were given the valley and much surrounding land after an act of bravery by a member of the court of King John. Alexander Lewius Peace; (sometimes known as Richard) was the family's first ancestor to come over to England with William the Conqueror after the Norman Invasion of 1066. He was named after one of two brothers; Walcheln and Josceln De Gulespin, or De Gylpin who took their name from the place in Normandy where they lived. Then around the time of the signing of the Magna Carta Richard de Gilpin, known as "Richard the Rider" accompanied the Baron of Kendal to Runnymeade because his secretary as the Baron was unable to read or write himself. After their return, Richard achieved renown for killing the Wild Boar of Westmorland a ferocious animal that had been terrorising the local villages. As a reward for his bravery, the Baron gave him the land in and around Kentmere, about 4000 acres (16 km²), described as "a breezy tract of pasture land" by the French Chronicler Froissart. From this time onward, the Gilpin's crest included a sable boar on a gold background. Many areas near and surrounding Kentmere still sport the name of Gilpin given to them by descendants of this family.

Richard's achievement and his ancestry were immortalised by minstrels of the period in a song known as "the Minstrels of Winandermere" after Windermere which is less than 10 miles (15 km) from the valley.

The estate of Kentmere was increased during the reign of Henry III by a grant of the Manor of Ulwithwaite to Richard, the grandson of the boar-slayer.

The family later became famous for their alliance with the neighbouring de Bruce family who went on to become ancestors of the Kings of Scotland.

Bernard Gilpin also known as the "Apostle of the North" was a youngest son of the Gilpins of Kentmere Hall during the 16th century, and grew up there. In his adulthood he stayed there on occasion, preaching at the church. Concerning Bernard Gilpin; Thomas Cox states:

:""Kontmire or Kentmeire, a small Village, famous only for the Birth of that eminent Person Bernard Gilpin, the Son of Edwin Gilpin, Esq; educated in Queens College, Oxford, where he proceeded Master of Arts, and was made Fellow thereof... This his Eminence in Learning recommended him to be chosen one of the Masters of Christ-Church, when it was first founded for a Dean, Canons, and Students by King Hen. VIIII, but he did not continue long there, his Mother's Uncle, Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham, sending him to travel.. Preaching he made his chief Business; and that the Gospel might be both thoroughly believed and practiced, he frequently preached as well in the remote Towns as near, insomuch that he was called, The Northern Apostle. His Alms also were so frequent, equal, and constant, that he was called The common Father of the Poor; and because a good Education of poor Children is one of the greatest Charities... he abounded in good Deeds, so he was careful not only to avoid all Evil, but all Suspicions of it, so that he was accounted a Saint by all that knew him, for Enemies he could have none. He died March 4, 1582, in the 66th Year of his Age, and came to his Grave like a Shock of Corn in its Season. He was buried in the Church of Houghton, and by his Will dated Octob. 17, 1582, he left Half his Goods to the Poor of his Parish, and the other Half for Scholars and Students in Oxford. He hath written several Things, but has nothing in print but a Sermon on St. Luke 2. 41, 48, preached before the King and Court at Greenwich on the first Sunday in Epiphany in 1552"::"Magna Britannica et Hibernia.Volume 6: Westmorland" by Thomas Cox (Vicar of Bromfield, Essex) 45 pages, printed in 1731

Bernard's oldest brother was George Gilpin who was commissioned by Queen Elizabeth I to form an alliance between the Dutch States and the English against the Spanish Armada. He was minister to the Hague during her reign. He carried with him an autographed letter written by the Queen stating:

:"Having charged Mr. Gilpin, one of our councilors of State, to deliver this letter, it will not be necessary to authorize him by any other confidence than what is already acquired by a long proof of his capacity and of his fidelity and sincerity, assuring you you may trust in him as in ourselves."

The second brother William Gilpin took residence in the mill in 1578 after marrying Elizabeth Washington of Hall Head (the great-great aunt of George Washington)

Kentmere hall remained in the hands of the Gilpins for 12 generations. It was lost during the English Civil War when Cromwell's troops destroyed the hall leaving only the fortified tower standing. The head of the household at that time left the land in trust to a friend and fled the country. When returning the gentleman's heir was unable to lay hold of the official deeds to the estate and so possession was lost. In 1660 ownership of the Hall passed to the Philipson family.

Minstrels of Winandermere Lyrics

:"Bert de Gylpyn drew of Normandie":"From Walchelin his gentle blood,":"Who haply hears, by Bewley's sea,":"The Angevins' bugles in the wood,":"His crest, the rebus of his name,":"Pineapple-a pine of gold":"Was it, his Norman shield,":"Sincere, in word and deed, his face extolled.":"But Richard having killed the boar":"With crested arm an olive shook,":"And sable boar on field of or":"For impress on his shield he took.":"And well he won his honest arms.":"And well he knew his Kentmore lands.":"He won them not in war's alarms,":"Nor dipt in human blood his hands."

::lyrics according to William Partridge Gilpin

The following lyrics were found by Reverend Charles Farish, whose mother was Elizabeth Gilpin (nee Washington). He claimed they dated to the 13th century.

:"At Crookbeck were his footsteps seen,":"The holy pilgrim he affrays;":"O waly, waly Kendal Green,":"And waly, waly Bowness braes!"

:"Ev'n when they kiss'd St Mary's ground.":"Them still their flutt'ring hearts misgave;":"They cast an eager glance around,":"Mistrusting every foam tusk'd wave."

:"For the wild boar is raging nigh,":"Bark'd are the trees about Boar-stile,":"At Underbarrow is his sty,":"Oh waly sweet St. Mary's Isle!"

:"But hark at Kendal rebecks sound,":"And Bowness Millbecks echo wakes,":"In Crookebeck ford he felt the wound,":"In death his burning thirst he slakes."

:"The gallant hero washed his spear,":"A tear unhidden left his eye,":"His faithful dog was bleeding near,":"The river stream'd with mingled dye."

:"And well he won his honest arms,":"And well he won his Kentmere lands;":"He won them not in wars alarms,":"Nor dipt in human strife his hands..."

(note; Charles Farish was a friend of William Wordsworth. In his book "Poetical Works vol. 1" a footnote to "Guilt and Sorrow; or, Incidents upon Salisbury Plain" states that some of its lines were taken "From a short MS. poem read to me when an under-graduate, by my schoolfellow and friend Charles Farish, long since deceased. The verses were by a brother of his, a man of promising genius, who died young."—"W. W. 1842" in a statement by the editor of the volume the footnote goes on to say that: "Charles Farish was the author of The Minstrels of Winandermere" as a result there is some debate as to authorship of the song commemorating Richard Gilpin's achievements).

Gilpin Coat of Arms

Or, a boar statant sable, langued and tusked gules. Crest: A dexter arm embowed I armor proper, the naked hand grasping a pine branch fesswise vert.

Motto: Dictis Factisque Simplex (Latin; "Honest in Word and Deed").

Gilpin Family Tree

*Walcheln De Gyplin or De Gulespin, brother Josceln. (possibly the same as, or descended from Walchelin de Ferrieres, Lord of Saint Hilaire de Ferriers, near Bernay, in Normandy).

*William de Guylpyn descendant married ___Bail.

*Bert (or Richard) de Guylpyn. son of William. Married A. Fleming. Came over from Normandy.

*William de Guylpyn - son of Richard. Married R./Elizabeth Lancaster.

*Richard de Gylpyn - "Richard the Rider" descendant, and first to live at Kentmere Hall.

*Richard de Gilpin - grandson of second Richard. Granted additional land by Henry III married Dorothy Thornborough?

*William Gilpin - son of Richard. Died 22 August 1485

*Edwin Gilpin - son of William. married Margaret Layton/Laton. :* - Eldest son George Gilpin - minister to the Hague during Queen Elizabeth I's reign.:* - Second son William Gilpin - married Elizabeth Washington the sister of George Washington's Great-grandfather.:* - Third son Bernard Gilpin (the "Apostle of the North") born 1517

*Martin Gilpin - son of William, married Catherine Newby, died 18 December 1629.

*Bernard Gilpin - son of Martin, born in Kentmere Hall 1552, married Dorothy Airey 1572, died 21rd April 1636.:*William Gilpin:*Martin Gilpin:*Francis Gilpin:*Samuel Gilpin:*Arthur Gilpin:*Randolph Gilpin:*Allen Gilpin

In the 13th.Century the Gilpin family lived in Kentmere Hall, near Kendal in the Lake District. King John granted Richard Gilpin the crest of a boar under an oak tree to honour his killing of a ferocious boar which was terrorising the neighbourhood.

Three centuries later, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, one of Richard’s descendants, Bernard Gilpin, became Rector of Houghton-le-Spring from 1557-1584.

Bernard was known as “The Apostle of the North” because of his evangelistic sorties on horseback through North East England.

He helped found Houghton’s Kepier School in 1574. He was a scholar and theologian who was politically not always on the popular side. He was only saved from trial and execution because the Queen died before he could reach London. His crest is now the logo of Houghton-le-Spring Rotary Club.

The Wild Boar of Westmorland is a legend concerning Richard de Gilpin and the villagers and pilgrims visiting the ruins of the Holy Cross at Plumgarths, and the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin on St. Mary's Isle on Windermere.

The story goes that in the reign of King John (1199-1216) a ferocious wild boar infested the forest between Kendal and Windermere, it had its den in the neighbourhood of the well known as Scout Scar. Tales of the monster’s malignant and unwonted ferocity were circulated far and wide, pilgrims paid their devotions at the Holy Cross before embarking upon the perilous journey through Crook and over Cleabarrow; the creature's main haunt. It is said that "inhabitants (of the local villages) were never safe from its attacks, and that pilgrims... shuddered with fear" 1. Richard De Gylpin determined to free them from these attacks, and tracked the monster through the forest. After a dramatic fight he slew the animal on the spot of the Wild Boar Inn, on the banks of the little stream, ever since known as the Gilpin. After these brave exploits Richard de Gilpin changed his family crest to include a black boar on a gold background. He was rewarded the lordship of the manor of Kentmere by the Baron of Kendal for his exploits. The event was immortalised in a song known as the Minstrels of Winandermere (see Gilpin family history for lyrics).

George Carlton, Bishop of Chichester (1619–1628), wrote a life of Richard's descendant the famous Bernard Gilpin, in it he said that Richard “slew a wild boar raging in the neighbouring mountains like the boar of Erymanthus, brought great damage upon the country people, and was as a reward for his services given the manor of Kentmere by the then Baron of Kendal.”

The Famous Wild Boar Hotel

Traditional 3 star hotel in tranquil surroundings close to Windermere

Set in the ancient beauty of the Gilpin Valley, this former Coaching Inn takes its name from the local legend of Sir Richard de Gilpin who bravely fought and killed a particularly ferocious wild boar close by. However its fame these days has much more to do with the warmest of welcomes, fine food served in a superb restaurant complemented by an extensive wine cellar, and an eclectic mix of cosy rooms and suites. Indeed The Famous Wild Boar has a very special quality that is often best experienced whilst relaxing by the open fire.

![]()

![]()

Article on Bernard Gilpin by local scholar, Dick Toy:

Spring came early in 1558. In Houghton churchyard, where the soil was regularly turned over by grave-diggers, bluebells followed daffodils, which followed crocuses, which followed snowdrops. The rooks built high in the trees, as if they had no expectation of high winds endangering their nests. By April, the call of the cuckoo was heard all around the town, disturbing contemplation and prayer (and other activities), and causing men to pay more attention to their wives, for fear of losing them to competitors.

There was also a new rector, Bernard Gilpin, appointed for the Parish of Houghton-le-Spring. Unlike William Franklin, who had been rector for thirty years, but who had never resided in the parish, and who, during the last twenty years or more, seems never even to have visited the place, Gilpin, it was understood, intended to live in Houghton. The Rectory, which had been in a woeful state for many years, was being reroofed and repaired, giving employment to workmen in the town, and was being got ready for the Rector to move in.

Down South, in London, Queen Mary was also in a buoyant mood, to match the Spring weather. King Felipe had briefly visited her in February, when his ship called in, in the Port of London, on one of his regular journeys between Madrid and Brussels. Now the Queen believed that she had at last conceived a son, before it was too late (she was forty-one years old by now).

She did not publicise the event so prominently as she had done in 1554, when she had had a false pregnancy, and her body had swelled up as if she were with child. Then she had delighted to stand sideways-on before her subjects, allowing them to see the swell of her belly. Then she had let it be known that she would appreciate christening gifts from her loyal subjects, for their future king, and the Palace had been flooded with bundles of baby clothing, either blue in colour, or in neutral shades which could be dyed either pink or blue; and also with children’s toys, particularly ones which were deemed suitable for boys. In the end, when her pregnancy proved false, they had all had to be given away. But now, in this glorious Spring of ’58, though she was more cautious in communicating her joy to the world, she felt it altogether appropriate that the body of the Queen of the land should be burgeoning with life.

(We know about the splendid Spring weather that year, as contemporaries commented on it, the climate having been spectacularly awful for many years up to 1558. Summers had been appalling, harvests had been ruined, and, during the latter years of Henry VIII, and the entire reigns of his son and daughter, Edward and Mary, the price of bread had risen uncontrollably, leading to great distress among the poor, even starvation for some. We do not of course know the reason why the weather deteriorated so markedly at that period : perhaps it was something to do with the sun-spot cycle; but humanity would not even know of the existence of sun-spots until the day when, fifty years later, Galileo would turn his telescope onto the Heavens.).

Presumably Mary was also satisfied with the pace of the process of “re-Catholicisation” that she was carrying out in the English Church. The worst heretics, she probably believed, had fled abroad, and there would be no more trouble from them. Those who remained were being brought before the Courts, and, if found guilty, were being condemned to the stake, and burned alive for the edification of others. It was an unpleasant business, but was necessary if England were to be reconciled to the Church.

Others were not so sure that things were going well. Edmund Bonner, the new Bishop of London (replacing Nicholas Ridley, who had been burned alive at Oxford) felt that the Church needed to be more resolute in purging itself of corrupted branches. He was aware that there were some areas of England and Wales where there had, as yet, been no martyrdoms. He had come to the conclusion that the defect in the system was that proceedings against alleged heretics had to be initiated in Bishops’ Courts; and some bishops were obviously reluctant to convene such a Court, and to initiate a heresy trial, even when very serious allegations were brought to their attention.

He had in mind particularly the Bishops of Bangor and of St. Asaph, in North Wales, and of Carlisle and of Durham, in the Far North of England. He therefore sought and secured powers from the Lord Chancellor’s Office, that he, Bishop Bonner, would be authorised to send out “runners” into the remotest parts of the Kingdom, in order to arrest men and women suspected of heresy, and to bring them to London, where they could be tried expeditiously, and, if found guilty, sent to the stake.

Probably very few people from London ever visited Bangor, or St. Asaph, or Carlisle. But the Prince-Bishopric of Durham was much more easily accessible. Durham was on the Great North Road, and couriers riding between London and Edinburgh regularly passed along the course of that highway. Also, London was becoming increasingly dependent on the Tyne for coal, that fuel which now warmed houses, cooked meals, and smelted iron and other metals. Colliers sailed regularly between the Thames and the Tyne, and it was easy for travellers to secure passage on these boats, and many Londoners could be met with on the streets of Newcastle.

Queen Mary was probably not much interested in Bonner’s plans to extend his jurisdiction into the remoter parts of her Kingdom. She much preferred the company of Cardinal Reginald Pole, the archbishop whom she had appointed to replace Cranmer at Canterbury. Pole was an elderly man, twenty years older than the Queen, but he seemed to be in many ways the very paragon of a Renaissance man. He had, in his younger days, been part of a circle of keen young scholars, and had mixed in the company of Erasmus, More and Tunstall - and of King Henry VIII. He had gained, at Padua, a degree in Law, and had been consulted by Henry, when the King wished to dispose of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and was looking for a good divorce lawyer.

Unfortunately, Reginald Pole informed the King that he would be unlikely to obtain a divorce. Henry was furious, and Pole found it necessary to flee abroad, to escape the King’s wrath. He went to Rome, and there learned that the King had revenged himself upon the Pole family by imprisoning them, and then executing them. His mother, Margaret Pole, as well as his brothers, had been beheaded.

He was appalled to learn that the execution of his mother had been entrusted to a new headsman, on his first day at work, and that the young man had only been able to sever Margaret’ head from her body with several blows of the axe. (Yes, it may be that, in King Henry’s time, a wise parent would be well advised to apprentice a bright son to the headsman’s trade : there always seemed to be plenty of work for headsmen in those days).

(Reginald must have blamed his own foolishness in giving such a negative reply to the King’s enquiry. But it might be that King Henry had another motive for ordering the extermination of the Pole family : the elimination of potential rivals to the House of Tudor. Margaret Pole’s maiden surname was Plantagenet, and that is of course a name which appears in English royalty centuries before the emergence of the Tudors).

In Italian exile in Rome, Reginald Pole, a graduate of an Italian university, was soon mixing with scholars and churchmen and even with Pope Paul III. The Pope made him a cardinal (though he was still only a layman), and then asked him to preside at an Ecumenical Council which he was intending to call.

The Council, which first met at Trentino, in the Italian Alps, in 1545 (in English, it is known as the Council of Trent) was originally intended to attempt a reconciliation between the Roman and the Lutheran Churches, but those Lutherans who had been invited wished to lay down unacceptable conditions for their attendance, and the Catholic delegates, meeting without them, passed their time by discussing tightening up the discipline of their clergy, and making administration more effective, as well as agreeing to jettison various practices, such as the sale of indulgences for money (the original cause of Martin Luther’s revolt) which, it was now realised, were indefensible.

The Fathers of Trentino had changed their position : from attempting to reconcile the Roman with the Lutheran Churches, to an attempt to bring about a rival sort of revolution within the Roman Catholic Church - a Counter- Reformation, in fact.

And when news arrived, in 1553, of King Edward’s death in England, and of Mary’s accession, and of what she was trying to do, they realised that the Kingdom of England was the “first fruits” of that Counter-Reformation.

Julius III, who had succeeded Pope Paul in 1550, immediately relieved Cardinal Pole of his Conciliar duties, and despatched him to England as Papal Legate, charged with overseeing reconciliation between England and the Holy See, and with meeting and supporting Queen Mary.

When Pole met the Queen, she informed him that Archbishop Cranmer had been “unfrocked” and imprisoned, and that she wanted Pole to succeed him as Primate of All England. He informed her that, though he was a cardinal, he was only a layman. Mary accordingly arranged for Bonner and two other bishops to meet her and Pole at Lambeth Palace, and, in three successive days, they presided at a series of ceremonies whereby Pole was successively ordained as deacon, priest and bishop, and then, the following week, he was installed at Canterbury as Archbishop.

Despite his new office, Reginald Pole now resided chiefly in London, advising Queen Mary on relations with Rome and Trentino (where the Council continued in session), and trying to introduce some of the reforms decreed by the Council, such as the requirement to establish a seminary, for the training of priests, in every diocese.

He also seems to have acted as the Queen’s spiritual adviser. He learned that she was growing increasingly alarmed about the development of her pregnancy. According to both the Court Physicians and to Ladies of the Court, things were not developing normally. The physicians dosed her constantly, and, whether or not they made things worse, they certainly didn’t seem to be able to improve her condition.

Her main fear at this time was not so much that her pregnancy was no pregnancy at all, but rather that, because of various developments, she might die in childbirth. Cardinal Pole advised her on drawing up a will, and in it she left the Kingdom to her child-to-be, and appointed her husband, King Felipe, the child’s guardian, until the child grew to be “of age”, and was able to rule the Kingdom in person.

That would indeed have been an attractive development from King Felipe’s point of view, but at that time he was experiencing increasing difficulties in his campaigns against King Henri II of France. By his marriage treaty with Mary, it had been agreed that England would not become involved in Spain’s wars in Europe (or in the Indies), but, so long as Felipe persisted in describing himself (among other titles) as “King of England”, his enemies would naturally see it as their right to make war on England.

Certainly King Henri saw it as his right and duty to attack England. He tried to endanger England by building up France’s traditional ally, Scotland. The sovereign of that country was her young queen, Mary, who had been only seven days old when her father, James V, died in 1542, and left her the Throne. Her position had been threatened by Protestant and other rebels, but a French fleet had arrived in Scotland, and had carried the young Queen to France, and there, in April, 1558, the girl was married to King Henri’s eldest son, the Dauphin François (Another wedding, a royal wedding, in that glorious Spring of ’58). French troops remained in Scotland, to help repel an anticipated English attack, and in addition the French seized Scarborough, to secure communications between France and Scotland.

King Henri also assembled troops for an attack upon Calais, the last English possession on the French mainland. Queen Mary of England realised that full-scale war was looming, but she lacked soldiers to fight for her, or money to pay them. In 1552 and 1554, we may remember, she had had no difficulty in obtaining help to suppress the attempts by John Dudley to place his daughter-in-law, Jane Grey, on the English Throne, or of Thomas Wyatt’s attempt to release Queen Jane from her prison in the Tower of London.

On both occasions, hundreds of armed gentlemen, not all of them by any means fervent Catholics, had leaped to Queen Mary’s support, and had saved her from her enemies. But now it seemed difficult for her to raise troops to defend Calais. Criminals had to be released from prison in order to muster sufficient men.

One force marched North to Scarborough, and recaptured that town without much difficulty. A much larger force landed at Calais, and, on hearing that King Henri was marching against them, they themselves marched out, and intercepted the King at a place called St. Quentin, and won a great victory.

Briefly the war was popular, and the victory was compared to those won at Crécy and Agincourt in the Hundred Years’ War; but the French rallied, and drove on until they had established gun emplacements which overlooked the Port of Calais, and prevented reinforcements or supplies reaching the English. Deprived of supplies, the English were forced to surrender, and King Henri declared Calais to be for ever part of the Kingdom of France.

Queen Mary, for her part, is said to have declared that the name of Calais would be for ever engraved upon her heart. Pole diplomatically changed the lament to say that the names of Calais and of Felipe would be forever on her heart. He presumably hoped that the King of Spain might be able to recover the city for his wife.

Many of Queen Mary’s subjects probably did not care one bit about Calais. They were more worried about the executions, the Fires of Smithfield.

And now, as we will relate next month, one man was on his way from Houghton to London, prepared if necessary to be a martyr. With men like Bishop Bonner at work, it seemed as if the burnings might never cease.

Dick Toy